One of the (very few) benefits of being in the business of capital markets and investing across more than three decades is the ability to quickly recognize the similarity of an event to something in the past. Or, in the case of this past week, the lack of similarity. The rapid unraveling of Silicon Valley Bank and the apparent encore of Signature Bank has people talking of 2008 and the Financial Crisis. It is actually hard for us to believe it has been around 15 years since the Crisis. It seems much more recently that we were standing with our colleagues watching Bloomberg screens of credit default swaps wondering who would fall next and what the likelihood was it would be our own employer. The whole system was unraveling. This is not that.

Superficially, there is enough in common to suggest history may not be repeating itself but at least it is rhyming. High-flying bank gets too far over its skis, customers and markets lose confidence, run on the bank, regulators step in and shut it down and look for a buyer. Looking another layer deep there is still some commonality – the bank failed at its most basic function, providing safekeeping of and access to customer money.

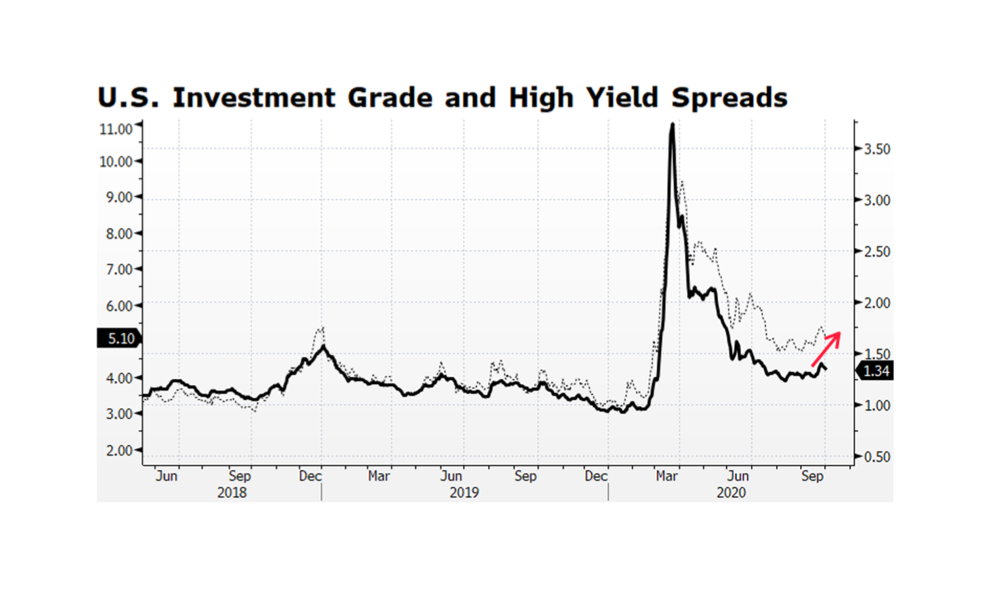

So, reasonably, people are concerned about contagion and a more widespread run on banks. But, unless some startling levels of as-yet unknown malfeasance or malpractice emerge to change the narrative, there is an important difference between what took down SVB and what took down Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, WaMu and others. In the depths of the Financial Crisis, the main problem was that nobody knew what bank balance sheets were actually worth. Complex securitized loan pools were valued based on assumptions and risk models that proved to be fragile or entirely wrong all at once. It wasn’t possible to look at these holdings and get even the slightest idea of what they were worth, which meant there was no way to understand how much capital the banks actually held against their depository and other obligations. The banks’ use of leverage also multiplied these unknowns making the consequences even more far reaching.

SVB on the other hand appears to be a good old fashioned case of staggering incompetence. Don’t get us wrong – that is no excuse. But in this case, it does not appear that the balance sheet of SVB cannot be valued. It is simply that they entirely blew the most basic and central internal role they needed to perform, which was to properly match assets and liabilities. They ended up with too many long-dated assets and short-dated liabilities and simply did not have the liquidity to satisfy customer demands that then blossomed into a run on the bank. By all accounts everybody knows what is on the balance sheet and what it is worth – and the answer is… not enough in the current market environment. Not zero, but not enough.

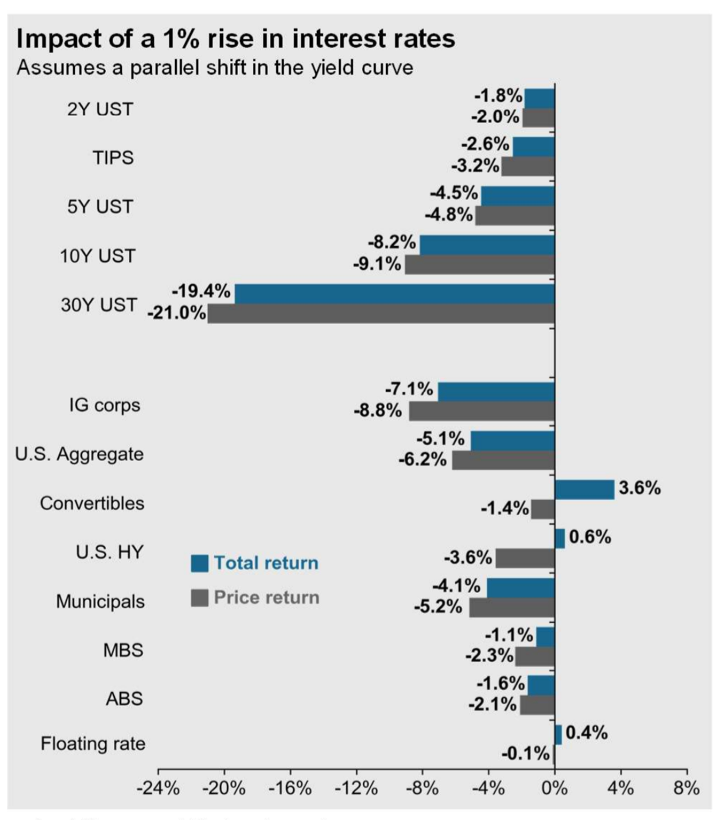

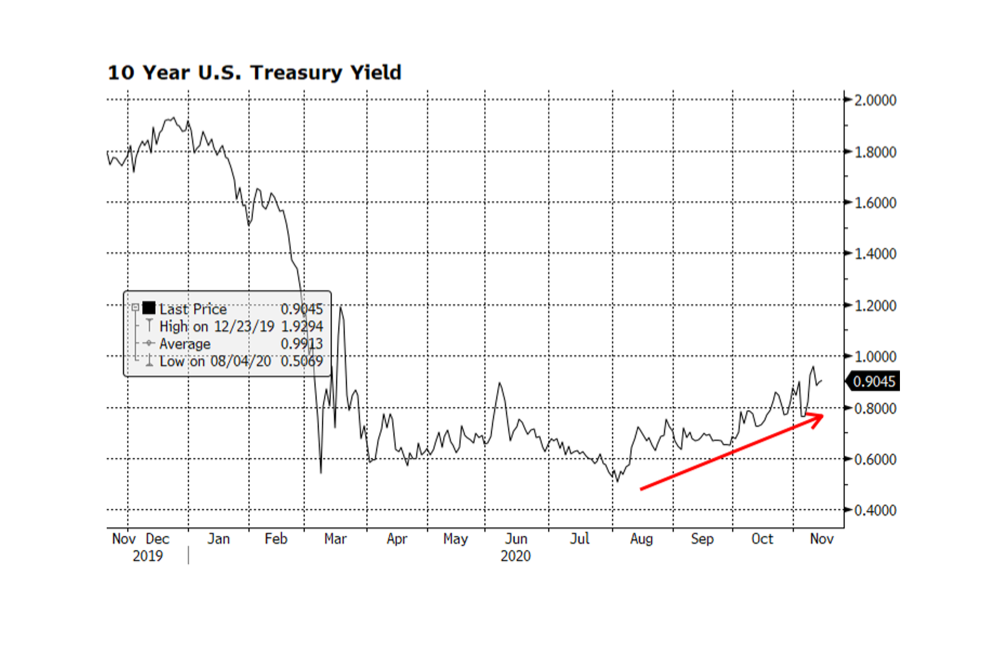

It also doesn’t appear that there is a quality issue like what plagued banks in 2008 where the securities on the books turned out to be far junkier than their ratings would suggest. They simply held too much high quality but long-dated Treasury and other obligations that got hit hard with the spike up in rates this past year. After the Crisis, the rules did change on what types of holdings counted and to what degree when assessing an institution’s capital adequacy. Treasuries are right at the top of the chart of holdings that satisfy those ratios. The bonds are still there, and there is no reason to think they wouldn’t pay out 100 cents on the dollar if held to maturity. But, SVB couldn’t sell them today to satisfy withdrawals for what they will be worth a decade from now. Again, basic asset-liability management seems to have eluded them.

Bank management may have assumed since cash was coming in hard and fast over the last couple years that liquidity was never going to be an issue, so they could step further out on duration to squeeze extra basis points of yield out of the balance sheet. A little stress testing would have shown that a meaningful rise in rates would hit the value of those long bonds, which meant everything rested on either the cash continuing to come in or at the very minimum their customers not looking for withdrawals in size. SVB, because of their business strategy, is unusually concentrated in its client exposure to the Tech and tech-adjacent sectors. It wasn’t a mystery that the whole Tech space was undergoing market stress, investors were tightening purse strings, and companies and their funders would be looking to tap their cash reserves to keep things going. They got caught in a simple squeeze – their principal clients needed to access liquidity at a time the bank couldn’t satisfy it without taking a hit on those assets.

As of late this weekend the regulators have stepped in and assured liquidity for all depositors, insured and uninsured. They do have a facility paid into by the banks that was set up precisely for this kind of situation. SVB (and Signature) is essentially defunct, and likely will be bought whole or in parts by one or more big, solvent institutions at a very attractive price and without having to assume the kind of risks banks faced buying the failed banks in 2008. In a bank run psychology does become reality, and even though the problems are not systemic in the way they were in the Financial Crisis, it is right and reasonable to be concerned about contagion. Customers could manufacture a crisis where one didn’t exist just out of fear. Regulators are doing the politically unpalatable and interceding in a way that will benefit a lot of unsympathetic parties in order to keep a very specific problem with a very specific group of institutions from blossoming into something much more damaging.

Dodd-Frank has never been popular, seen as too odious and heavy-handed and in the way of free enterprise in the view of industry stakeholders, and with the benefit of more than a decade in use it could definitely be improved. However, this past week serves as a graphic example of why it is necessary, and why regulation and supervision are essential to the orderly functioning of our financial systems. In the all-too-apropos words of the comedian Ron White, there’s no cure for stupid.