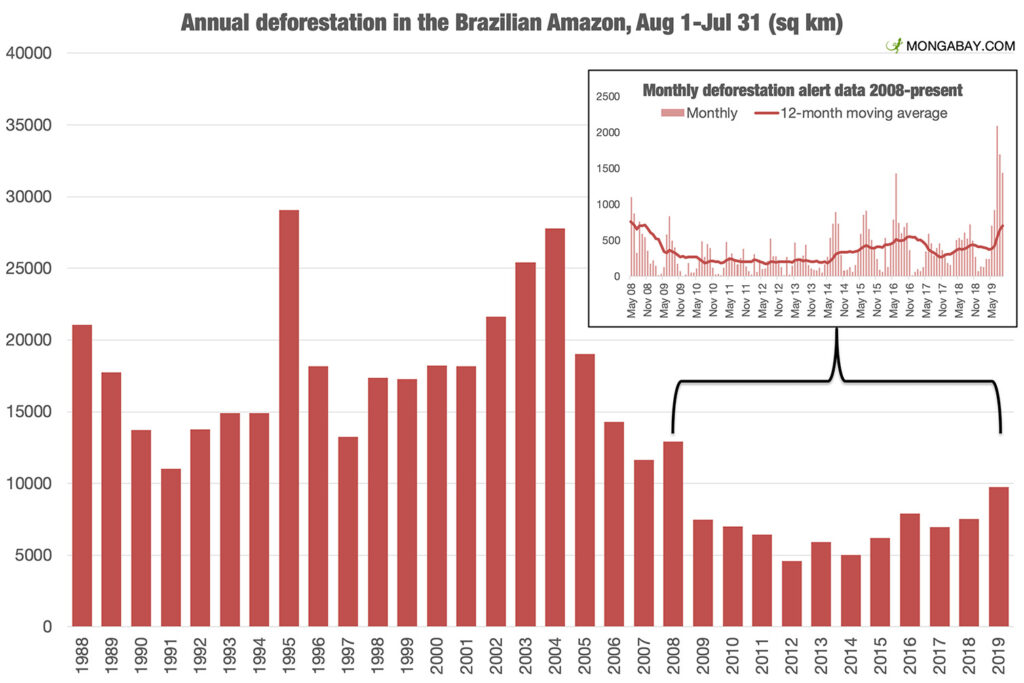

Jair Bolsonaro isn’t there either. While the President of Brazil is not in attendance, the country is still represented, but one is forced to wonder what the degree of commitment is when the boss chooses not to attend for “strategic” reasons. On the positive side of the ledger, even with Bolsonaro’s absence Brazil signed on to the pledge between 100 signatory countries to end deforestation by 2030. And reinforcing our point about the real action being with private enterprise and not with government, dozens of global financial services companies also are committing to discontinue investment in and financing for businesses and other concerns engaging in or profiting from deforestation. Today’s charts look at the trends and patterns in Amazonian deforestation. Brazil made great positive strides over the past decade dramatically improving over the prior twenty years. However, with Bolsonaro’s election we observe a significant jump in activity in 2019, and expect similar increases in 2020 and 2021 (not yet reflected in the data). The second chart from NASA provides a visual representation of reduction in vegetation in the Amazon in a period between 2000 and 2008 to illustrate the patterns of destruction. Ironically, note that the pattern looks like leaf veins, propagating from main roads to local roads and spreading out into the forest until larger and larger tracts of land are cleared. Crops like soy account for much of the native vegetation cleared, and one of the biggest importers of Brazilian soy in the last couple years is China. No Bolsonaro. No Xi. Starting to see a pattern there too?