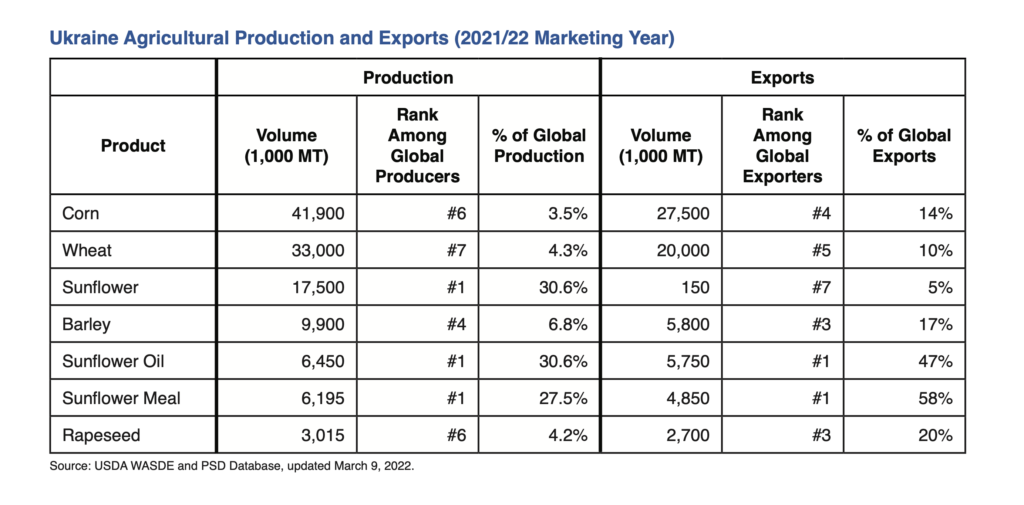

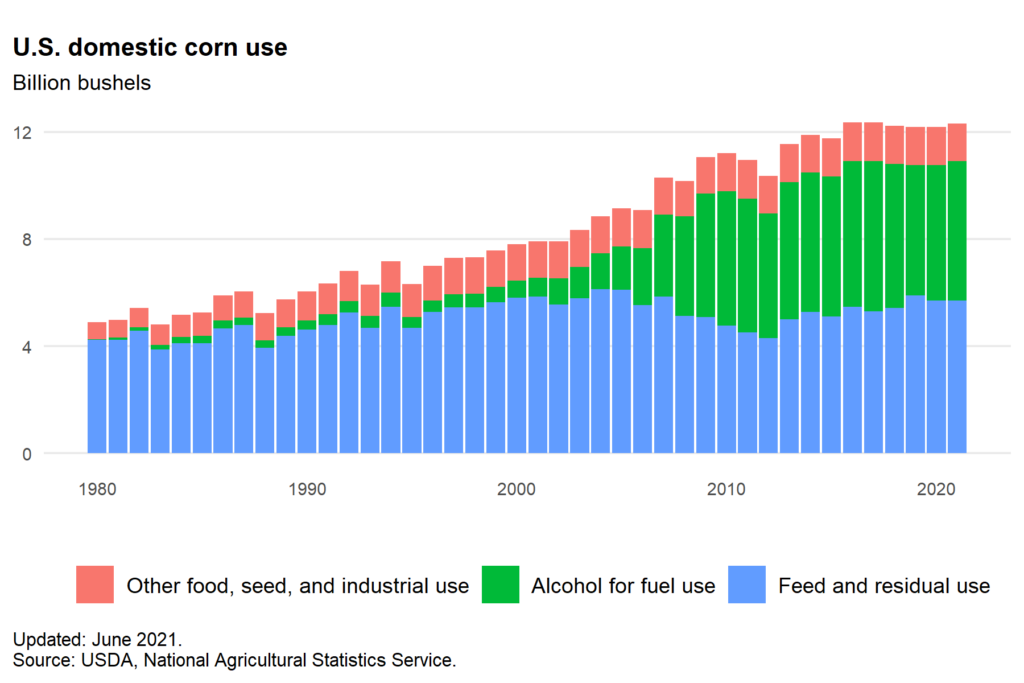

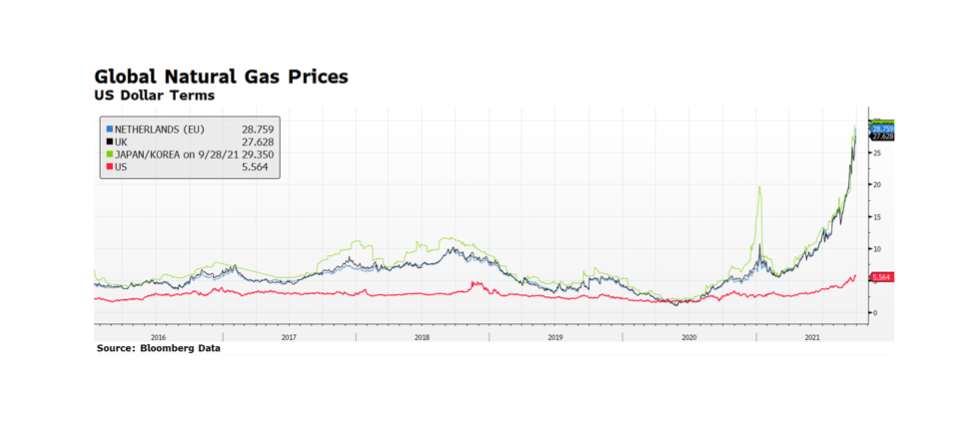

Let’s talk about something that proves that short-sighted or wrong-headed decisionmaking in ESG is bipartisan. One of the incredibly unfortunate halo effects of the Ukraine conflict is the global food shortage caused by Europe’s breadbasket being at war and the sanctions limiting access to Russian natural gas (key source for fertilizer). In addition to placing at risk a large percentage of the world population that are already nutritionally insecure, it has the effect of driving up commodity and food prices in the developed West. As we have discussed in prior blogs and newsletters, the conflict has also destabilized the petroleum market because of Russia’s role as a petrostate. The US is effectively energy independent, or nearly so if we look at all of North America together, but no question energy prices are higher. So what’s an American to do in the face of a global food and energy crisis? The US administration has an answer – put food in your gas tank. The decision to move to E15, 15% anhydrous denatured alcohol in the fuel mix, for the Summer arguably makes the whole situation worse. Referring to the US Energy Information Administration, the ASTM D4806 specification for ethanol compatible with spark-ignition engines is produced by “fermenting the sugar in the starches of grains such as corn, sorghum, and barley, and the sugar in sugar cane and sugar beets”. The first chart is from the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service and shows just how material Ukraine is to the global food supply. The second from the USDA statistics service shows already how much US corn production goes to fuel. There is a whole additional discussion to be had about the sense or senselessness of grain and cane crops being turned into fuel, from the energy intensity of the chemical conversion to the natural gas used to make fertilizer to the diesel burned for farm equipment to the climate costs of unsustainable monocrop farming practices that strongly suggests shortening the path from drill bit to burner tip is more efficient. But right now, we are focusing on the fact the US could (profitably) ameliorate rising food scarcity and prices with the same agricultural products it is planning to ferment and burn to save 10 cents on a $5 gallon of gas at the pump.