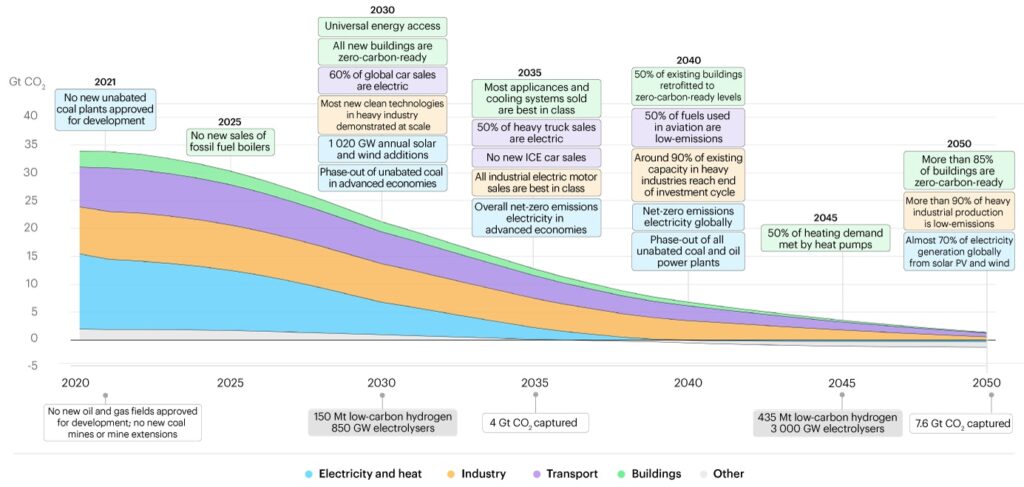

Yesterday a consortium of mostly Anglo and European countries signed a statement affirming a commitment to “deliver sustainable, green and inclusive economic growth to meet the challenge of decarbonising our economies, in line with limiting the global average temperature increase to 1.5°C above the preindustrial levels.” The statement covers six categories of targets — Support for workers in the transition to new jobs, social dialogue and stakeholder engagement, economic strategies, local, inclusive, and decent work, supply chains, and Paris Agreement reporting. The important thing we note in this statement is the recognition of the necessity of public/private partnership. The path to zero requires industry and market-wide activation of capital and corporate infrastructure in the private sector and regulatory and reporting frameworks from the public sector that facilitate the private sector’s work. This chart from a May 2021 International Energy Agency (IEA) report “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for Global Energy Sector” provides an excellent overview of the business and industry targets that must be met with the facilitation and support of both governments and NGOs over the next 30 years. The signatories to the statement make sense in that these are many of the wealthiest industrialized nations that have both the capital to pursue this agenda and a high degree of responsibility for having brought us to the climate precipice. However, the lack of presence from Australia, China and Japan is concerning as they must help lead among the community of nations as the most developed and prosperous (polluting) countries of the Asia-Pacific region.