Climate change has pervasive and profound consequences for our planet, economies, and cultures. The systems of climate do not discriminate across racial lines, income levels, or geographical locations, nor abide by governmental policies and regulations. But it is important to draw a distinction between the worsening storms, sea level rise, drought, fire, ice loss and mass extinctions that occur on a planetary level, and the injustice of more prosperous businesses, communities, and nations driving that climate change and imperiling already marginalized communities at home and abroad. We lay witness to social, economic, public health, and environmental effects disproportionately impacting vulnerable and underprivileged populations. We acknowledge these inequalities of influence, largely on minority and low-income communities, as climate or environmental (in)justice.

Continued increases in global warming contribute to already existing challenges in eradicating poverty, reducing inequalities, and ensuring healthy individuals and ecosystems due to higher food insecurity and reduced water supply, community income losses, lost livelihood opportunities, adverse health impacts and population displacements, and increased competition for arable land. Poverty and disadvantage are projected to rise in some populations due to increased global warming. Some of the most severe impacts of climate change and a lack of climate resiliency are expected to be felt among agricultural and coastal dependent regions, indigenous people, children and the elderly, poor laborers and urban dwellers in African cities, and people and ecosystems in the Arctic and Small Island Developing States (SIDS), dryland regions, and least developed countries (IPCC, 2018).

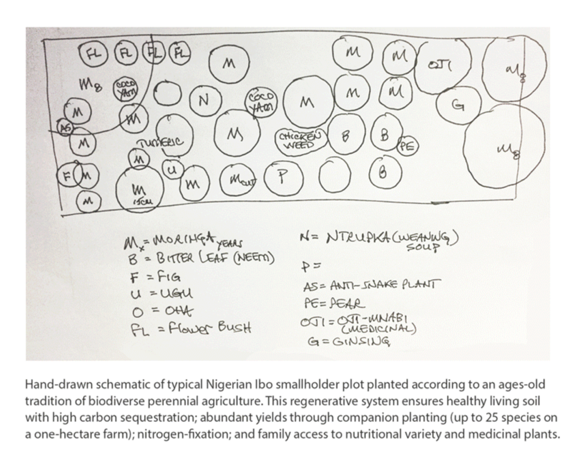

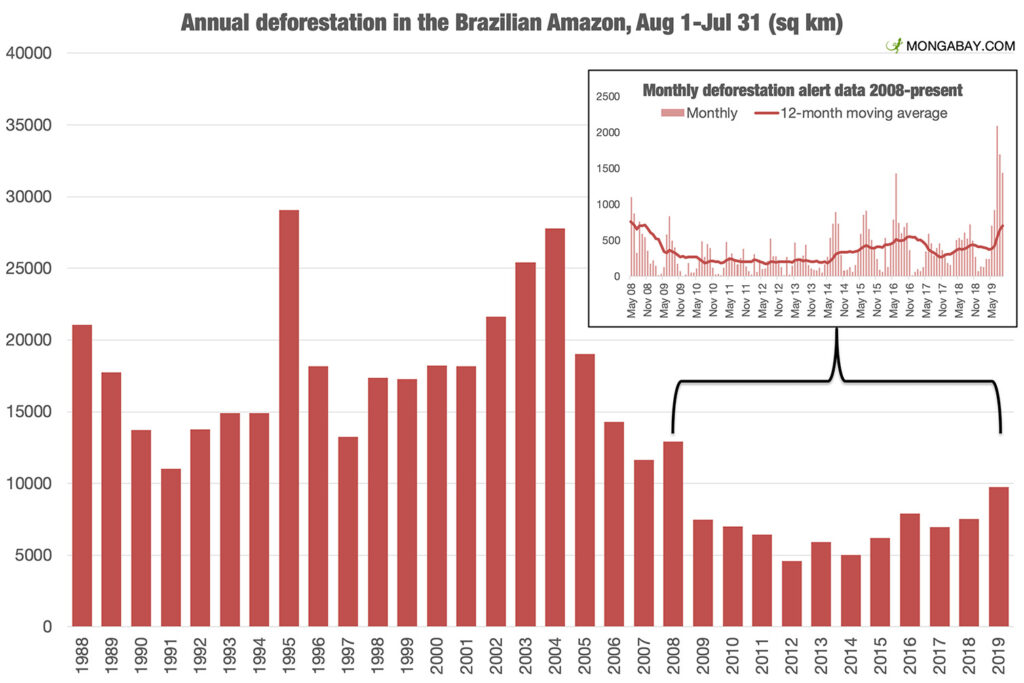

For example, land degradation refers to the deterioration of soil quality due to both natural and anthropic impacts, accelerated during the 20th and 21st centuries as a result of increasing agricultural and livestock production, urbanization, deforestation, and extreme weather events such as droughts and coastal surges. Land degradation occurs over 25 percent of the Earth’s ice-free land area, affecting 1.3 to 3.2 billion people, the majority of whom are living in poverty in developing countries (IPCC). Land degradation and climate change, both independently and in conjunction, have severe consequences for natural resource-based regions including higher threats of malnutrition, increased risk of water and food borne diseases resulting from poor hygiene and lack of clean water, increased respiratory diseases due to atmospheric dust from wind erosion and air pollutants, and spread of infectious diseases as communities experience lack of food production and are forced to migrate to more hospitable regions (WHO, 2020).

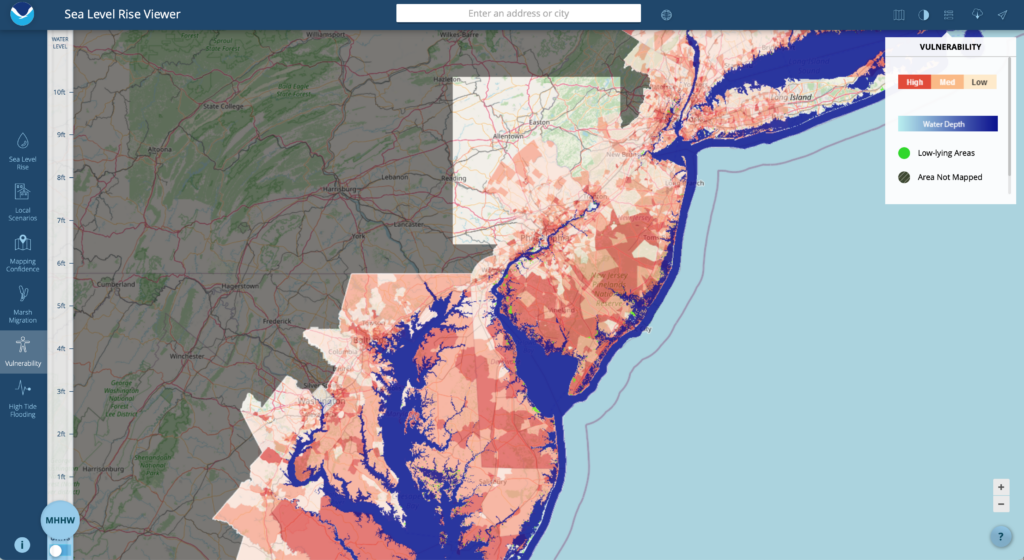

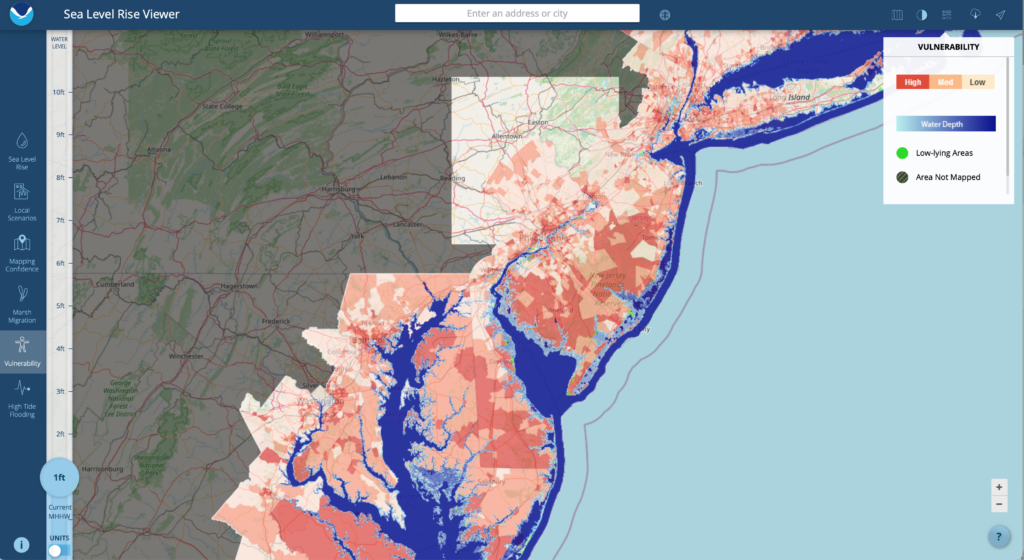

Furthermore, increasing global warming intensifies the exposure of small islands, low-lying coastal areas, and deltas to the hazards related to rising sea levels including increased saltwater intrusion, flooding and damage to infrastructure, loss of coastal resources, and a reduction in the productivity of fisheries and aquaculture. One global fishery model projected a decrease in global annual catch for marine fisheries of about 1.5 million tonnes for 1.5°C of global warming, with a loss of more than 3 million tonnes for 2°C of global warming. The risk of irreversible loss of many marine and coastal ecosystems escalates with global warming, specifically coral reefs which are projected to decline by a further 70–90% at 1.5°C and larger losses (>99%) at 2°C warming. Furthermore, changing ocean biochemistry due to increased acidification adversely affects marine species’ physiology, survivorship, habitat, reproduction, and disease incidence, and increases the risk of invasive species. Risks from vector-borne diseases, such as malaria and dengue fever, are projected to increase with warming in addition to potential shifts in their geographic range (IPCC, 2018).

In addition to global warming and changing ecosystems, global industries also contribute to environmental injustice. Oil exploration and drilling fields have produced severe impacts on indigenous peoples and vulnerable communities around the world who depend on healthy ecosystems to survive. Oil drilling in the Amazon basin spurs deforestation of the land, introduces toxic pollutants impacting indigenous peoples’ health and wellness, and allows for hazardous working conditions for local employees. Incursions into indigenous lands are frequent and have been recorded in more than 20 communities in at least 10 countries including the United States, Australia, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Peru (UN, 2021).

Closer to home, labor groups in Louisiana have reported dangerous working conditions in oil refineries, as they emit numerous types of toxic chemicals including benzene, formaldehyde, hydrogen sulfide, sulfur dioxide, and sulfuric acid. Oil production companies, although permitted to release these chemicals to the environment in designated amounts, are plagued with accidental spills and leaks often exceeding the allowable volumes. This toxic contamination puts nearby communities at high risk of environmental health problems. Additionally, in regions where fracking is used as a method to extract shale gas, such as Pennsylvania, surface and well waters are continually contaminated with the toxic chemicals used in fracking fluids and petrochemical run-off including salts, heavy metals, and radioactive chemicals. Oil pollution contaminates both drinking and agricultural water supplies for livestock and irrigation, which has been found to be particularly detrimental in the Melut Basin of South Sudan in Africa (UN, 2021).

Oil refineries and other chemical releasing facilities are predominantly surrounded by minority populations. Communities located in close proximity to such facilities, coined “fenceline communities”, are exposed to various kinds of toxic pollution, and in the U.S. are disproportionately composed of African Americans, Latinos, and low-income groups. The highest concentration of U.S. oil refineries is located in the Gulf of Mexico, with one of the most notable fenceline communities residing outside Houston, Texas. Three quarters of the city’s residents live within three miles of the 191 hazardous chemical facilities and are known to be at higher risk for heart disease, cancer, and respiratory problems related to poor air quality, such as asthma and emphysema. The combination of lack of access to healthy food, high poverty rates, and increased exposure to deadly contaminants makes for a serious problem in fenceline vulnerable communities, especially African Americans. Fenceline communities are found in many states across the U.S. as well as globally (UN, 2021).

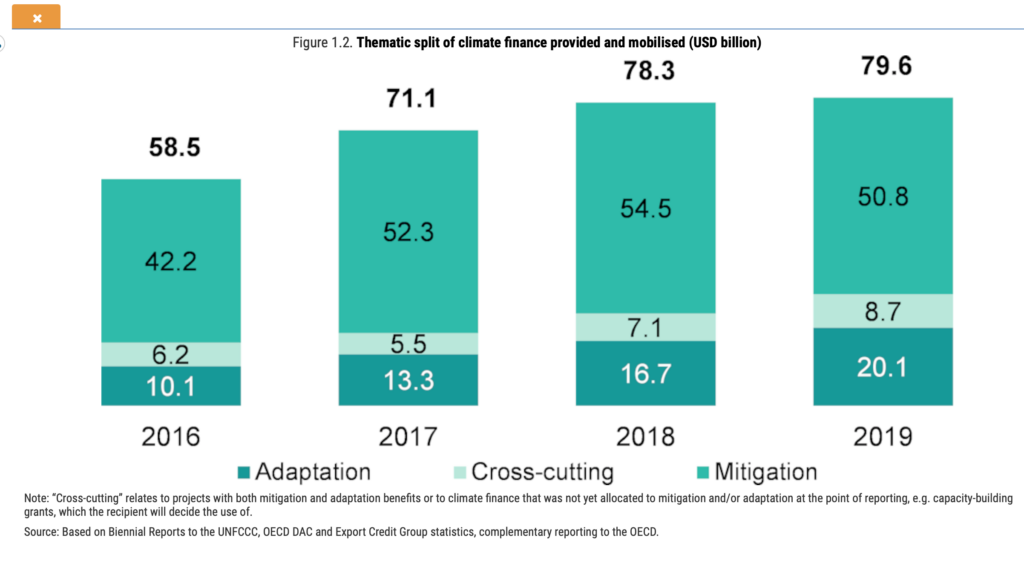

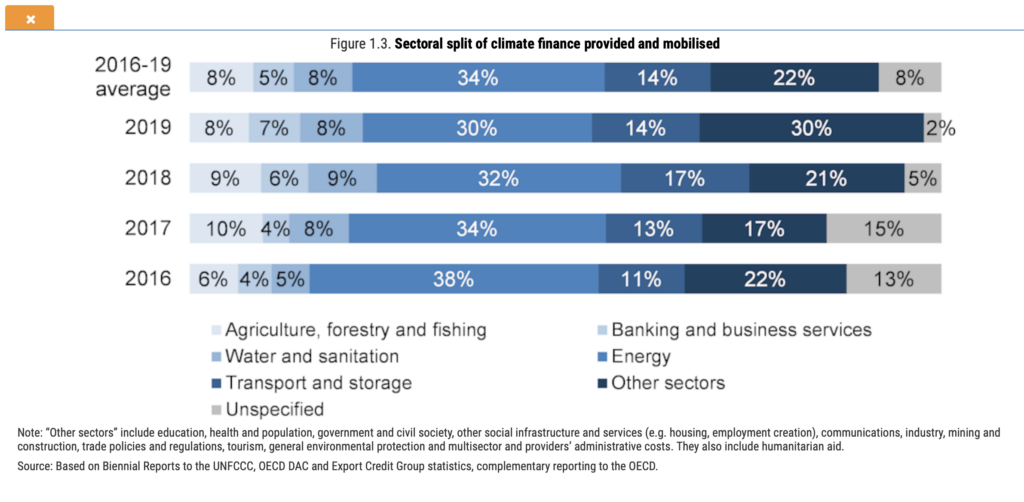

We have also observed a trebling effect with fenceline and other economically disadvantaged communities when climate change and environmental pollution collide. Storm surge, inundation, flood, and wind often cause this pollution to breach containment and further toxify neighborhoods and cities, waterways and water supplies, and farmable land as with Hurricane Katrina in 2005in Louisiana and Harvey and Imelda in 2017 and 2019 in Houston, TX. These types of climate-related disruptions cause communities to fracture as vulnerable people move to seek cleaner, safer, healthier, more sustaining situations. This destabilization can lead to diasporas, conflict and even war, as well as the disintegration of cultures and art. From port cities to open grasslands to the frozen tundra, the ability to be resilient and adaptive in the face of these environmental and climate forces requires access to capital and opportunity. Even better, developed economies taking their collective foot off the literal and figurative gas pedal will help to manage down the risk and give these at-risk communities a shot at better outcomes. Climate justice involves doing both. Less extractive and more regenerative. Systems that work on a global level for the benefit and welfare of all.

Climate justice gives us the words and concepts to frame and then address countless intertwined challenges that affect access to nutrition, access to clean water, access to education, access to economic opportunity, an expectation of peace and prosperity, and the ability and in fact the right to care for our collective legacy and culture and gift it to the generations that come after. Our final discussion for ESG Week is with Professor Warren Senders of the New England Conservatory of Music. We explore the interconnectedness of climate science, indigenous wisdom, and world art and culture, and our collective responsibility to care for the planet we have, and to care equitably and justly for the people on it.

https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/climate-change-land-degradation-and-desertification

https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/SR15_Full_Report_High_Res.pdf

https://wedocs.unep.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/35417/EJIPP.pdf