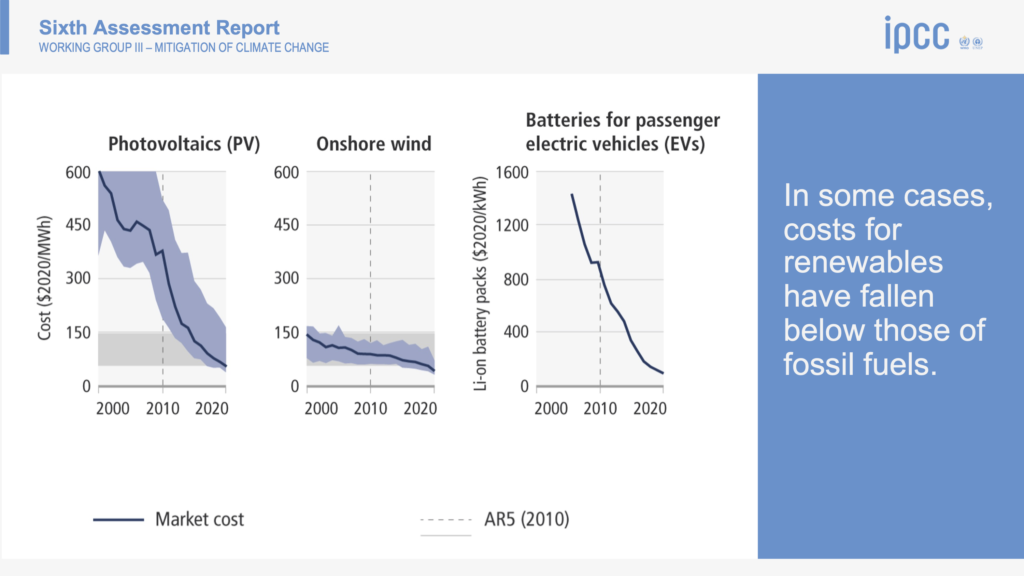

With the release of “Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of climate change”, which is the third segment of this year’s sixth assessment report (AR6) from the IPCC, most of the attention will be focused again on the doomsday charts. One of the notable ones in the press packet is entitled “We are not on track to limit warming to 1.5 (deg) C.” But, the report is surprisingly optimistic in one very critical sense – it declares the problem addressable if global action is taken promptly and capital is called in off the sidelines to drive a transition in energy, land use, industry, urban zones, buildings and transportation that could halve GhG emissions by 2030. At this point the debate then usually swings to the nature of capitalist systems and that capital will flow to where it can be used most efficiently and to greatest effect (e.g. risk-adjusted return), and there it stops. Advocates for changing policy on climate will trot out the “if we don’t act we’ll all die and your money won’t mean anything” argument, having failed to learn that existential threats don’t tend to deter markets until they become existential realities, supporting a party-like-it’s-1999 mentality. However, one slide in the press packet which probably won’t get much attention actually holds the key to activating capital entitled “(In some cases) costs for renewables have fallen below those of fossil fuels.” This is profound in that it doesn’t require the rest of the science or policy or existential concerns to affect the flow of capital. It is simply becoming cheaper to convert today’s sunshine and wind into electricity and shove it into batteries than to dig up fossilized sunshine from more than 65 million years ago and burn it. Even with investment and innovation in efficiency, modern society will continue to be increasingly energy intensive, and as more of the world’s population joins the middle class, utilization will become even more widespread. Intelligent allocators of capital will pursue the cheaper inputs that will meet that demand.